All of the above.

At its most basic, S. is sold as a book. It comes as a book inside a slipcover, sealed in cellophane. The slipcover is black with a large, gothic "S." printed on it--also in black. there is a sticker that holds the book inside the cover, printed with a monkey on the front side, with the names of the co-creators. On the back is an impressive masted ship. These are not random images.

Inside is a book that has been carefully constructed to look like a vintage library book. The cloth cover is drab, the graphics are definitely mid-century. Ship of Theseus, by V.M. Straka. There is even a Dewey Decimal sticker on the spine, listing it as "813.54 STR 1949."

[But this might be an error! Dewey number 813. 54 is for "American literature in English, 1945-1999," but the whole point of the book is that Straka is unknown--but none of the leading "candidates" for being Straka is American. Furthermore, the book was translated by the mysterious F.X. Caldeira. So the call number is wrong for Ship of Theseus (should be somewhere in the 890s perhaps), although it is closer to right for S. Of course, the number for S. should be "813.55 ABR 2013." Hmmmmm.]

The library motif continues inside, with browned pages, a "stamp" printed on the inside cover "BOOK FOR LOAN" and a replica of due date stamps in the back, showing desultory borrowing from 1957 and ending in 2000. Patrons are instructed to "KEEP THIS BOOK CLEAN"--pencil marks or other defacement to be reported to the librarian.

[I distinctly remember being told by the school librarian at my elementary school that we were expected to wash our hands before reading library books. We were even issued oil skin book bags to carry our books home from school to keep them safe from the weather. Even then, I thought it was nuts--and I continued to read library books at the table while I ate lunch.]

Already, this review has become even more digressive than most of my others. I am chalking this up to the power of the physical object--the book, not just the words inside it, is really the topic of this project. It is a love letter to the book as object.

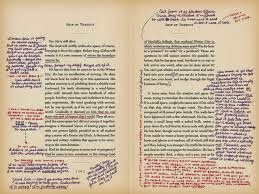

Take a look at a "typical" page.

The text of the novel "Ship of Theseus" is the work of mysterious author V.M. Straka, a writer of 19 books whose real identity is unknown. The authorship controversy is more popular than the actual novels. Ship of Theseus is his last book--he reportedly died in 1946, in Havana, and some of the last chapter of this book was lost. He may have been killed. The book was originally written in Czech (I think?), and translated by F. X. Caldeira, who wrote an introduction and the footnotes. Caldeira was the sole translator of Straka's works from 1924 on, but never met the writer in person. Caldeira is supposed to be a Brazilian who died in his own home town in 1964.

The margin notes come in five different sets, representing five different time periods.

- First are penciled marks and brief remarks, made by Eric at about age 16. He stole the book from the library--so presumably his is the last due date stamped in the back, October 14, 2000.

- Twelve years later, Eric's book is found by Jen Hardway, an undergraduate at the (fictional) Pollard State University, who works at the library. Jen found the book, read a few chapters and returned the book to a library workroom with a note. She and Eric begin passing the book between them, making notes in blue cursive (Jen) and black block letters (Eric).

- Later, Jen switches to yellow, and Eric responds in green.

- Still later, Jen writes in purple, Eric in red.

- Finally, they both write in black ink.

At any given time on the page, you might be reading from any of these five time periods, plus Caldeira's editorial notations. Add in the original text, and suddenly as a reader, you are keeping track of seven different time streams.

It's almost like Minard's famous map of Napoleon's Russian Campaign of 1812.

The timeline is even more complicated, if you accept that Caldeira and Straka exchanged drafts of the work, translating even before the book was complete--and that Caldeira finally ended up reconstructing or inventing parts of the incomplete final chapter.

So what is this book? What has V.M. Straka written that has caused academics to search for his true identity? It intrigued Jen enough that she started corresponding with Eric (the owner of the book) and soon burned through all nineteen of Straka's works.

Good question. What Dorst has done is create a convincing pastiche of early 20th century modernist political literature. Ship of Theseus is, on it's surface, the story of the amnesiac "S," a man who arrives in the Old Quarter of a town identified only as "B--." He is wet, has apparently just come out of the sea, and has nothing but a stack of papers in his coat pocket, marked with the gothic "S."

[Later, we learn about "Santorini Men," named after the first one discovered on a beach on the Greek island--anonymous, unidentifiable men found murdered, dumped into the sea, and containing only pages from Straka novels in their overcoat pockets. S. is probably a Santorini man who managed to survive--a fact that is not explained to the reader. S's page is folded and wet, soaked into an indistinct mass, marked with the Gothic S. He believes if he could read those pages, he might discover something of his identity and past. He might, if S is a fictionalized Straka--it's perhaps a clue to who S is supposed to be, but one he never solves for himself.]

He lurches through an eccentrically populated town, ending up in a bar where there is a very ominous and unsettling bit of writing describing the brutal form of capitalism practiced in this world:

Several hundred yards ahead, a recent immigrant who speaks the language only haltingly enters a storefront to return a rented barrel organ. The owner. . .takes the organ from the immigrant, and leans it against a wall along with the eighteen other organs that he rents each morning to other just-as-recent and just-as-tone-deaf immigrants. He holds out his palm for his half of the organ-grinder's take.

The organ-grinder does not yet understand the local currency, so eh hands his cigar box of coins to the owner, asks him via hand gestures and sentence fragments to do the stacking and splitting for him. The owner makes two piles. He pushes the taller stack across the table to the organ-grinder. The shorter stack, which is worth much more (this, apparently, being a city of ancient and flawed arithmetics as well), he sweeps into an open drawer.

The organ-grinder, who understood when he rented the organ that this unscrupulous man would cheat him at any opportunity, has anticipated such a trick and has stashed away a portion of the day's take. Those coins, wrapped inside a handkerchief, are snug in the pocket of the tattered red coat worn by his capuchin monkey….The owner, of course, suspect that the organ-grinder has done this. It's not a new trick to him. Once the immigrant leaves the shop, the owner will direct his slow-witted but strong armed sons to follow the man through the night, as long as it takes, until he gives himself away--perhaps when he ducks into an alley beside a tern and empties the monkey's pockets, at which point the sons will hold him down in the street and crush his wrist bones to dust with led pipes. They will catch the fleeing monkey by it's rope and try to sell the beast inside the tavern. No one will want it, of course. . .Eventually, the brothers--now quite drunk--will go out to the docks, tie something heavy to the other end of the rope, and test how well monkeys can swim.A spiral of deception and greed, then ends to no one's benefit. The owner gets additional coins, but no further rentals from this man, the man's ability to work is destroyed, and the monkey dies. Only the brutish sons benefit, in that they get to become drunk.

[This is, in miniature, the theme of Straka's work. It is no coincidence that there are nineteen organs to rent--nineteen is a recurring number that stands for Straka's group of radical labor activists, who constitute a group called (confusingly) "The S" in Straka's "real" life. So the Ship of Theseus novel is in some ways Straka's project to document the history of "The S" with it's losses and turncoats. The story of the organ renter is replicated in the larger story of the protests against the arms manufacturer Edvar Vevoda--which is itself a fictionalization of Straka's efforts against arms manufacturer Bouchard.]

S enters a tavern, sees a beautiful woman reading Don Quixote, and then gets shanghaied onto a boat. The boat has nineteen sailors, who all have their mouths sewn shut, but who spend their off duty time writing. Time passes differently on the boat, so when S next lands, several years have passed. He gets swept up into a demonstration against Vevoda which turns deadly. Vevoda's own brown coats plant a bomb to discredit the labor movement. S escapes with four labor organizers (who are versions of Straka's own compatriots). In their attempt to escape, the other four are all killed. Only S survives, and when he returns to the ship, there are only 15 sailors.

The story continues with eerie occurrences, semi-magical locations, and S's own obsession with the woman from the tavern who has several names. S muses on his own identity--will he be able to remember who he is, or is he only who he has become? "Ship of Theseus" is a philosophical conundrum, like "my grandfather's axe"--if you replace all the pieces of the ship, is it still the same ship? ("This is my grandfather's axe--I replaced the handle and my father replaced the head." Is it?) If S replaces whoever he had been with all the actions he takes in the book, does the old S even exist any more?

If is were a "real" novel, really written by a writer named Straka, it's not something that would interest me particularly, because it's a justification of why labor has to take up arms against capitalists, and Straka apparently murdered a fair number of people in his day. It reads like early 20th century political struggles that ended with the recognition of the right to unionize. Important, certainly. Timely again, as "right to work" laws proliferate and union membership drops. It's kind of an extended self-justification, and not a topic I would pick to read myself, even with the eerie fantastical elements.

But that is not the whole story.

There are several other stories superimposed on this one--"Palimpsest upon palimpsest" as the book puts it at one point. The first additional story, chronologically, is that of F.X. Caldeira, the translator of the book. Popularly supposed to be a man, over the course of the book Jen and Eric discover that F.X. is actually Filomena Caldeira, a woman who apparently carried an unrequited love for Straka for decades, despite never having met him. Her footnotes in this volume are eccentric, and are revealed to be coded messages for Straka, published in the belief that his Havana death in 1946 was a hoax and that he might look for her. She passes on some information about who was the mole in "The S" who gave away some of their members. She codes her love for Straka and where she might be found. She "reconstructs" the final chapter of Ship of Theseus to give her doppelgänger a happy ending with S.

Eric tracks her down, as she is still alive and alert, and answers some of Eric's questions. In the course of the Jen/Eric correspondence, she dies, perhaps the last living link to Straka.

There are other stories, all conveyed in the Jen/Eric marginalia. Chronologically, the earliest is the story of Eric, a grad student working on the question of Straka's real identity. There is apparently no locatable biographical evidence of Straka's existence, and the authorship questions has grown to eclipse the study of the novels themselves. Eric's advisor is a professor named Moody, and he had a relationship with a fellow grad student named Ilsa. By the time the J/E correspondence begins, Eric has been disgraced and expelled from the school. Moody has apparently stolen Eric's scholarship, with Ilsa's help, in order to bring out his own work on the authorship question. Eric acted out, vandalized one of the buildings on campus, and ended up in a mental hospital for a while. Now, he haunts the campus, trying to avoid being reported, while he continues to work on the question of "who was Straka?"

After getting interested in Straka's works, Jen becomes his co-conspirator. She is suffering from a serious case of senior slump, and finds renewed passion in reading Straka's novels and working out Caldeira's embedded ciphers. Her coursework suffers, her parents worry and attempt to intervene. Her interest in Straka gets Ilsa's attention, and there are some threats to her own safety. Jen reports that a barn on her parents' property was burned down, and that she is being spied on and followed. Ilsa suspects her of academic dishonesty and she is called to a disciplinary hearing. J/E interpret this as being orchestrated by Moody to silence them and promote his own theory.

I felt this part was pretty unbelievable. It parallels the way Vevoda chased S, but S really did pose a threat to Vevoda's business model. I'm not sure the stakes of academia are convincingly high to justify such cutthroat tactics. (I'm not convinced they are that high, especially in literature departments, but I don't think Dorst has written this believably enough to cause me to suspend my skepticism.)

The academic espionage continues with Straka artifacts going missing from international archives, and the mysterious death of a French professor soon after his own book on Straka's real identity is published. There is a mysterious "Serin Institute" that starts funding Eric, but it's not clear who they are or why they care about Straka at all.

Jen and Eric parse the text of Ship of Theseus, drawing the parallels between characters and real life Straka associates. They notice the number of them who died from mysterious falls--perhaps Bouchard is still in business and still sending agents to silence them? Are those same agents after J/E? Is "Straka" just the pen name of all the members of "The S," and are the nineteen novels ascribed to him each written by a different person? If so, does this make Filomena Caldeira the real organizer?

Meanwhile, Jen and Eric use phrases of the novel to spark their own conversations, revealing their histories, arranging secretive meetings (in the back row of a theater showing noir films, of course!) and ultimately falling in love. In deliberate counterpoint to the Straka/Caldeira story, J/E get a happy ending. Jen finishes her coursework, doesn't get disciplined, and graduates. She and Eric move to Prague to pursue writing their own book about Straka's identity. Their last marginalia is written with a shared pen, in a shared apartment--sort of a nostalgic activity.

In addition to all of that, of course, are the many pieces of ephemera interleaved in the book. This is where the valentine nature of this product really shows through--all the different types of materials are faithfully reproduced. A campus map drawn on a cafeteria napkin is really on a napkin, one printed with the fictional logo of Pollard State University no less. Business cards feel different from postcards, which are different from the several pages of lined notepad paper. This is not so much a "love letter to the written word" (as it says on the back of the slipcover), but a love letter to the idea of a BOOK--the physical artifact. The differing colors of ink, the different handwriting styles, the way it physically holds their letters and postcard to each other--this is something that simply cannot be replicated by an ebook.

(There is apparently an ebook, which does allow for erasing the marginalia, if you want a clean copy of the Straka novel for some reason. There is also apparently an audiobook, and I have NO IDEA how they are going to pull that one off!)

So in the end--what do we have? We have a commitment to the idea of the book as a physical object. We have a demonstration of how a book (and writing) can contain multiple time streams, how it conveys and preserves ideas and personalities over time. It offers explicit and implicit puzzles, recording and enacting (for real readers in real time) how stories can engage us and how we work to solve the puzzles of literature.

I have some questions that I don't have the answers to yet.

- Does each chapter have a cipher? Several of them are solved by Jen and Eric in the margins, but there are several where they indicate that they suspect a cipher, but can't find the key to unlock it. S.Files22 has catalogued the known ciphers, and is working on finding and solving others, including one using the Eotvos Wheel that comes in the back of the book but isn't used by Jen or Eric. http://sfiles22.blogspot.com

- Does the book solve the mystery of Straka? It's clear that J/E have their own belief, but isn't that ambiguous? Is that a solvable mystery within the game of "S."?

- Were there agents after Jen? Is there a conspiracy of violence to keep Straka's identity hidden, even in 2012? If so, who is it?

- What happened to the nineteen pieces of obsidian that disappeared from international archives?

- Is there some master intelligence behind the happenings of the book?

In the end, it may boil down to the messiness of human effort. Even S realizes that the distinctions between the good guys and the bad guys is blurred. Both have adopted the Santorini Man gambit, leaving their enemies dead with Straka pages in their pockets. One side intended it as a message, the other side adopted it to demonstrate their ability to contaminate the message. By the end of the book, there is no way to tell which is responsible for which murders. Identity is unknowable.

I suspect this is a message about Straka--his identity is unknowable, but what is on the page can be loved. Not a bad meta-message at all.

__________

P.S.

In a book as full of explicit puzzles as this, there will of course be internet communities and commentary that will serve as a locus for like minded readers who are examining the mysteries. So far, these are the two most interesting that I have found.

The Eotvos Wheel: what appears to be created in conjunction with the book--ostensibly amateur scholarship on V.M. Straka, with crime scene photographs of the Havana hotel room where Straka [may have] died in 1946, a list of the candidates for the "real" Straka. Interestingly, the blog has a few entries dated 2009, and then lay fallow until new postings began in November 2013, after the publication of the book. http://eotvoswheel.com

S.Files22: apparently a reader created site which documents many of the idiosyncrasies of the book and is working to find and solve any additional ciphers not revealed in the Eric/Jen notes to the text. http://sfiles22.blogspot.com